EU Audit shows agriculture and forestry policy not strong enough to fight climate crisis

- EU Court of Auditors says agriculture and forestry sectors need to improve EU GHG emissions reporting

- Greater action and stronger policy is needed in order to meet GHG emission targets

- The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), Europe’s most expensive and controversial policy, has no vision to shift to a zero carbon economy

Meeting reporting requirements is one thing, but on climate, reducing emissions is what really matters.

If you ignore the 173 million hectares of agricultural land and 134 million hectares of managed (and often burnt) forests, the latest audit of European Union (EU) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reporting* has found the books are somewhat in order. However, the books also show that without drastic changes to climate, energy and land use policy, the EU will not meet its emission reductions targets for 2030 and 2050.

*The Member States in the sample were Czechia, Germany, France, Italy, Poland and Romania. They produced 56 % of EU emissions in 2016.

The European Court of Auditors have today (20/11/19) released a report answering the following question: Does the Commission appropriately check the EU greenhouse gas inventory and the information on future emission reductions? It was found that data reporting is generally in line with UNFCCC requirements, but improvement is needed in the land use and forestry sectors and better insight is required for future greenhouse gas emission reductions.

Some key findings of the audit concerning climate and land use policy are outlined below.

EU GHG emission reduction targets will not be achieved without firmer mitigation policies

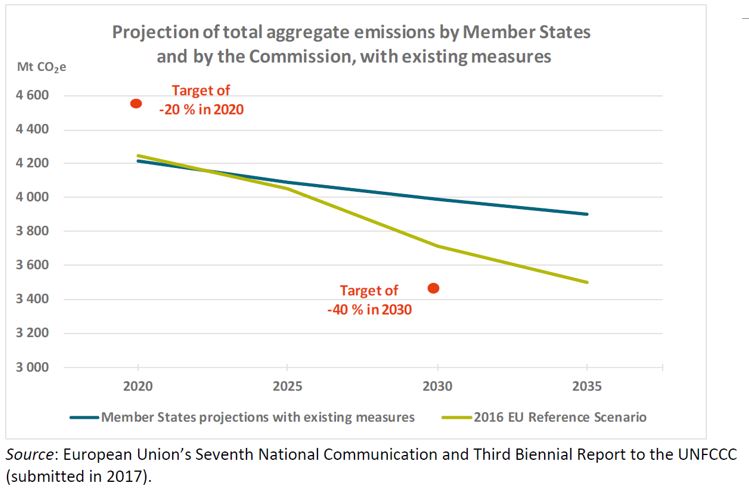

In 2016, the Commission produced an EU Reference Scenario predicting future GHG emissions under the assumption of full enforcement of the current mitigation policies and measures, and achievement of the emission reductions proposed by these measures. At the time, the Reference Scenario would not have achieved the target of 40% emissions reduction compared to 1990 levels by 2030. Worryingly, the audit found that information reported by the Commission to the UNFCCC shows that combined Member States’ projections beyond 2023 will now achieve even lower emission reductions – a risk that the Commission has not assessed.

The Commission needs to take leadership and set a clear pathway for MS in reporting and modelling

The audit found that as a result of incomplete reporting by the Commission, the reports to the UNFCCC do not present a complete view of the contribution of the EU and Member State policies to the intended emission reductions for 2020, 2030 and 2050. Leadership needs to be taken by the Commission and these shortcomings rectified in the ongoing development and review of National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) and Member State Long Term Strategies (LTS).

The incoming Commission needs to get serious about climate change

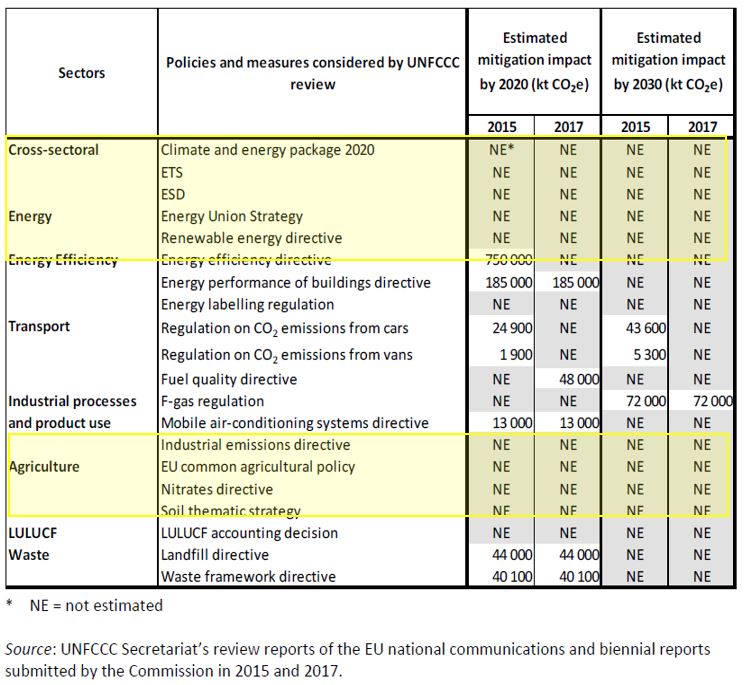

The audit found that Member States reported limited information on the estimated effects of national mitigation policies on greenhouse gas emissions despite Kyoto Protocol and UNFCCC requirements to do so, whilst the Commission itself assessed significant environmental and climate impacts for less than half of relevant EU policies. Quantified emissions reduction and other climate indicators both signalled by the Environmental Agency and recommended by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2014 are yet to be implemented.

As per the table, the previous Commission was seemingly going backwards, with fewer estimations provided in 2017 than in 2015, with the Agriculture, LULUCF (Land use, Land use change and Forestry), Renewable energy directive, and Climate and energy package 2020 all notably not estimated.

The Commission needs to improve the review process for the land use and forestry sectors

The Court of Auditors report recommends that the Commission should update its review guidelines for inventories to strengthen checks in the LULUCF sector and align them with those made in the other sectors.

What is the LULUCF sector?

Vegetation and soil accumulates atmospheric CO2 and stores it as carbon. Land use, land use change and forestry can cause carbon to be released from these stores through practises such as tree harvesting for energy, or when land is cleared or ploughed for agriculture. Conversely, carbon stores increase as forests grow. Carbon accounting in the LULUCF sector is the balance of carbon released into the atmosphere (e.g. by cutting down trees) minus the amount of carbon removed from the atmosphere and stored (e.g. by trees growing). If this number is positive, the LULUCF sector is a net emitter of carbon into the atmosphere, whilst if this number is negative it is defined as a carbon sink.

Currently, the changes in forestland are accounted and reported under the Kyoto Protocol and UNFCCC commitments. However, under the new LULUCF Regulation in 2018, adopted following the Paris Agreement, emissions and removals from forest management, grasslands, croplands, wetlands and settlements will be mandatory to report. With a review of monitoring, assessment and reporting in the sector to be carried out accordingly.

Long-term vision and emissions reductions targets needed as part of the Common Agricultural Policy

Despite the Commission communication – A Clean Planet for all, the audit found that roadmaps to define long-term objectives for the sustainable development in accordance with the EU 2050 climate commitments, and set a direction for shorter-term sectoral policies and measures were missing from the agriculture and LULUCF sectors.

Strikingly, the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP), currently being renewed for the period 2021-2027, was found to not have a long-term vision, and despite its stated aims fails to contribute to climate action or specific emission reductions. Similarly, the current EU forests strategy works on 7-year cycles with the current strategy finishing in 2020. In light of the LULUCF sectors inclusion in the 2030 emissions reductions targets the audit recommends medium- and long-term forest strategies.

A carbon sink or sinking peatland and forest void of biodiversity?

The audit found that in 2017 the LULUCF sector removed 5.54 % of the EU CO₂ emissions from the atmosphere, thus acting as a carbon sink. However, the audit notes that LULUCF data has high statistical uncertainty. Such uncertainty party comes through difficulty in quantifying carbon stocks, which is made worse by scant forest definitions allowing completely clear cut and thinned forest areas to be deemed the same as high-carbon stock old growth forests. Heightened uncertainty is due to a lack of transparency in the sector, with an NGO review of Member State National Energy and Climate Plans to 2030 finding alarming information gaps in the sourcing, projected use of forest biomass, particularly for bioenergy, and often absent emissions accounting.

In its 2030 targets, the EU introduced what is called the ‘no debit rule’, requiring that Member States have no increase in the emissions from this sector compared to a baseline. Unfortunately, with 64% of EU renewable energy coming from bioenergy, this has seemingly been interpreted as it being okay to burn what grows above this baseline. Alternatively, increases in carbon stores within the LULUCF sector have come from the planting of monoculture forests, often at the expense of carbon rich peatlands, biodiversity and other land uses.

Non-audit conclusion

The European Court of Auditors report makes it clear that the land use and forestry sectors cannot be relied on by other sectors to pick up the slack of weak emission reduction pathways, whilst clear long term vision for climate action is needed in agriculture and forestry. Such vision should include measures to enhance and protect terrestrial carbon sinks through natural restoration of wetlands and peatlands, and the protection of forests which are not routinely managed, in order to allow carbon stocks to build over time.

Furthermore, the Commission needs to provide leadership to both its Member States and at a global level to ensure that the strategic emission reduction plans contribute to achieving the 2030 and 2050 reduction targets, and verifying that Member States set out appropriate policies and measures for sectors in line with their long-term strategies.

Reference of the European Court of Auditors report referred to in the text as ‘the audit’ and Milionis et al. (2019):

Milionis, N., Sniter, K., Tartaggia, M., Markus, R., Dumitrescu, O., Roşca, L., Laanes, L., Krzempek, N., Tanguy, B., Moore, R., & Pyper, M. Special Report No.18 – EU greenhouse gas emissions: Well reported, but better insight needed into future reductions. European Court of Auditors, Audit Chamber I Sustainable use of natural resources, Luxembourg. 2019