OF CLEARCUTS & BIRDS #4

LATVIA

Through the voices of our local Partners, our series “of clearcuts and birds” tells some of the stories of Finnish, Estonian and Latvian forests and of their incredible biodiversity, as well as the hard consequences of their exploitations, (in)directly driven by the EU’s support for bioenergy.

If left to nature, Latvia would be almost entirely covered by forests. Most Latvian forests are classified as ‘modified natural’ or ‘semi-natural’ forests. These are made up of native tree species, though they may have been thinned or even planted, and have some of the characteristics of undisturbed natural forests.

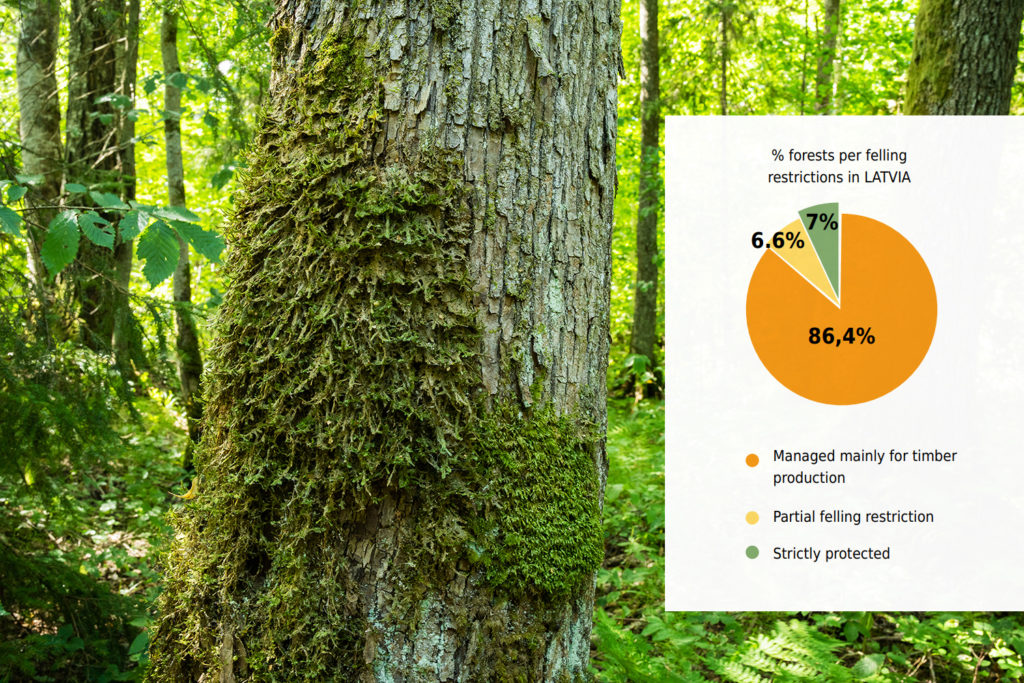

While the total area classified as “forest” has remained stable or has even slightly increased (depending on the data source), the actual tree cover has declined. 86.4% of Latvian forests are primarily managed for timber production, with clearcuts as the main practice in the final “harvest”. This has dire impacts on forests, birds,and biodiversity. Let’s hear the stories of our local colleagues.

A LITTLE BACKGROUND IN LATVIAN FORESTRY

According to Global Forest Watch, Latvia is the second European country and the 20th in the world with the highest loss of relative tree cover from 2001 to 2021. Carbon sequestration in forests has been declining due to increasing harvesting levels. Since the 90s, the national forest carbon sinks have been reduced by two-thirds. This has a direct consequence on climate, as carbon sinks from Land Use Change and Forestry sector (LULUCF) swing to a net carbon source.

The Baltic region is known as one of the world’s largest outputs of wood pellets. Latvia remains one of the largest producers in the region with an output of around 1.6 million tonnes in 2018 and 2019. The country supplies by itself at least 23% of the Dutch consumption of wood pellets.

From 2016 to 2018, the harvested forest areas increased by 32% in Latvia in comparison to the period between 2004 and 2015. Viesturs Kerus, CEO at Latvian Ornithological Society (LOB – BirdLife Latvia), analyses: “Some data sources give the impression that the forest cover in Latvia has increased, but one should beware of what is considered as forest. Knowing that clearcut areas are officially counted as forests, we understand why the total forest area seems to continue to increase… In reality, the area of forest that is older than 20 years is steadily declining since at least 2008.”

Only 7% of forests are strictly protected in Latvia and partial felling restrictions apply to only 6.6%. Viesturs comments: “With only 11.5%, Latvia has the second lowest coverage of Natura 2000 sites in the EU after Denmark. But even within Natura 2000 sites you will be able to find a lot of clearcuts, as is the case for the Nīcgales meži or Forests of Nīcgale. While one of the conservation goals of this area is the protection of forests, it has been heavily logged during the past 20 years. And this is just one example. However, it is worth designating Natura 2000 areas for forest protection because, though not perfect, they still ensure better protection than outside these territories. “Nīcgales meži” is a bad example but there are also good ones.”

What’s more, over 80% of the total final felling – logging oriented to harvest mature trees – takes the form of clearcuts in Latvia, rather than selective logging. Viesturs concludes, “despite all the proof that the state of our forests is worrying, the government of Latvia recently decided to lower the limits for the final felling of pine, spruce and birch forests, which are most of the forests in Latvia. They claim that this will ensure there is enough forest biomass for heating during the war of Russia in Ukraine. Allowing to harvest thinner trees means that younger forests will be cut, as there is a strong relation between forests age and trees size. We expect that this decision will increase logging rates and consequently have dire impacts on forest biodiversity.”

THE PROTECTION OF FOREST BIODIVERSITY

In 2019, Latvia and Estonia together exported three million tonnes of wood pellet, made from six million m³ of wood. This is equivalent to 200 km² of clearcut or twice the size of Paris. High demand for wood has affected the last remaining old growth forests in Latvia. But these forests play a crucial role in biodiversity conservation.

Viesturs explains: “Old-growth forests are unique biodiversity hotspots. Deadwood, large old trees, trees with cavities and other micro-habitats host a variety of species that cannot survive in actively managed forest landscapes, such as the Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), the Black Stork (Ciconia nigra) and hundreds of species of moss, fungi, and lichen.”

“In Latvia, habitats listed in Annex I of the EU Habitats Directive (see table) have recently been mapped out. But large parts of them are still not designated as Natura 2000 sites, putting the decision of whether or not to log a site in the hand of forest managers. This results in the destruction of valuable habitats all over Latvia.”

| The EU Habitats Directive: The Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora aims to promote the maintenance of biodiversity targeting a list of habitats and species. Annex I includes the natural habitat types of community interest whose conservation requires the designation of special areas of conservation. |

Since 2015, LOB maintains a breeding bird monitoring scheme, covering about half of all bird species breeding in Latvia. Viesturs explains: “The Hazel Grouse (Bonasa bonasia) population has decreased by 93% between 2005 and 2018. The Hazel Grouse is a resident forest bird species and is listed in the Annex I of Birds Directive. While this bird has suffered from the most dramatic decline, several other forest bird species, like the Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo), the Lesser Spotted Woodpecker (Dryobates minor) or the Willow Tit (Poecile montanus), are also declining.”

“For a set list of species (e.g. Black Stork (Ciconia nigra), Lesser Spotted Eagle (Clanga pomarina) and Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus)) the law in Latvia allows the designation of small protected areas (micro reserves) in breeding sites. We actively make use of this option and thanks to our work many micro reserves have already been successfully designated.”

“But there is still a lot of work to be done,” Viesturs concludes. “Besides working on specific sites, we actively advocate for more sustainable forestry across Latvia. To achieve this, we closely collaborate with other environmental NGOs, in particular with the Latvian Fund for Nature and Pasaules Dabas Fonds. Sadly, preserving the status quo is most often the only result of heavy fights with forestry sector, whose only objective is to have even more intensive forestry in Latvia.”

THE LESSER SPOTTED EAGLE NESTS DESTROYED BY LOGGING

It is estimated that around a third of the Lesser Spotted Eagle (Clanga pomarina) population in Europe, and almost a fifth of its world population, breeds in Latvia.. However, the Lesser Spotted Eagle population decreased by about 15% in Latvia since the end of the 90s, followed by some recovery later. The LIFE Project ‘Conservation arrangements for Lesser Spotted Eagle in Latvia’ was led by the Latvian Fund for Nature (LFN), with the partnership of Latvian Ornithological Society. The conclusions were released in 2021.

Over the course of four years, 543 new Lesser Spotted Eagle nests have been found, of which roughly 10 % have been adversely affected by forestry activities. This includes cases of destruction of nesting sites, including felling of nesting trees, or cases where logging is planned without considering the presence of a Lesser Spotted Eagle.

Jānis Ķuze, project manager for Latvian Fund for Nature, clarifies: “Currently only 6% of the Latvian Lesser Spotted Eagle population nests inside Natura 2000 territories. Thereby micro-reserves are the most suitable conservation tool to protect their breeding sites as well as other dispersedly nested bird species in Latvia. The essence of the problem is that there are no mandatory assessments in place to identify the nature values of forests before felling them. They should be put in place like the assessments that exists to identify the economic values of a forest.”

| Forest stand was logged down during the breeding season of the Lesser Spotted Eagle, which resulted in unsuccessful breeding. By law, it is required to leave the trees with large nests and encircling group of trees in the clear-felled areas although it has a rather limited value. This is illustrated by the aforementioned case, where the nest was left overexposed and was abandoned. Picture taken at the end of the breeding season on 01.09.2018. (Pictures by project LIFE AQPOM, Latvian Fund for Nature) |

When nests are discovered, protecting them is not easy. “The process of establishing micro-reserves for the protection of nests provoked a sharp reaction from forest owners’ organizations”, details Jānis, “The main objections were that private forest owners do not receive adequate compensation for restrictions on economic activities in micro-reserve territories and they don’t feel sufficiently involved in the establishment process of the reserves.”

While the birds are protected on paper, nest trees are still cut every year. Jānis Ķuze concludes, “the data collected during the project on the destroyed nests have been transferred by the Latvian Fund for Nature and the Latvian Ornithological Society to the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development and the Ministry of Agriculture. Since no action was taken by the state institutions, the Latvian Fund for Nature has prepared and submitted a complaint to the European Commission regarding the violation of the Birds Directive.”

Interviews by Julien Bacus. Pictures by Karl Adami .

A huge thanks to Viesturs Kerus and Jānis Ķuze for their testimonies and their precious help during the edition of this article.

INTRO – EU FORESTS

FINLAND